Managing Memory during ML Compilation

Been a while since I posted; but I was busy settling into my new (old) job at Apple :-). In this post I want to share some tips I picked up during a recent effort optimizing the memory footprint of our ML compilation toolchain. Without getting into proprietary specifics, these are some general pitfalls and ideas that apply to almost anyone building or debugging ML infra.

The irony is that we often run out of memory just *trying* to load the model and compile it, long before we ever get to run it on the constrained target device. Here is how I’ve been tackling that.

Meta models

During compilation, a model usually goes through various “representations”, from the source (usually something like HuggingFace) to your custom framework, like say LiteRT (formerly TFLite) or ExecuTorch.

There may be re-authored PyTorch versions too, as I mentioned in my previous blog on exporting MambaV2 for `ai-edge-torch`.

The standard approach to initializing a model object is often something like model = MyModel().eval(). But doing this even a couple of times when you are dealing with a large LLM can eventually cause an OOM (Out Of Memory) error on a standard dev machine even as hugginface is loading all the shards.

The idea here is to use a model representation that contains just the pertinent metadata about the computational graph without “fleshing it out” with training-specific weights (which are the heavy part). You can use such a representation for a lot of initial analyses and graph passes too.

In PyTorch, this is implemented natively using the meta device. On a meta device, a model gets populated with “fake” tensors that have shapes/dtypes but allocate no physical memory. It is possible to even invoke such a model—with fake tensors, of course—to trace the graph.

import torch

# Context manager ensures layers are initialized on 'meta' device

# No RAM is allocated for weights!

with torch.device("meta"):

model = MyTransformer(config)

# Verify it works with fake inputs

fake_input = torch.randn(1, 128, 768, device="meta")

output = model(fake_input)

print(f"Output shape: {output.shape}")

# Output shape: torch.Size([1, 128, 50257])However, there is a catch. You usually want to eventually “populate” such a model by associating the meta weights with real weights, especially if you want to use something like torch.export to actually lower the model.

One must also be careful with sub-modules that rely on constants created during module initialization—data that isn’t present in the generic state dict. A common culprit is Rotary Positional Embeddings (RoPE). If those cos and sin tables are on the meta device, you might crash your compiler (since it sees no real data) OR get random values in your final artifact (since the meta device doesn’t construct real tensors).

A good idea is to explicitly initialize such tensors inside a with torch.device(”cpu”) scope within your module. This takes precedence over the top-level meta device initialization.

Here is what that looks like in a simplified RoPE implementation:

class RotaryEmbedding(torch.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, dim, max_seq_len=2048):

super().__init__()

# We force these constants to be on CPU (real memory),

# even if the model is initialized under device('meta').

# This is crucial for graph tracing that needs actual values for shapes.

with torch.device("cpu"):

inv_freq = 1.0 / (10000 ** (torch.arange(0, dim, 2).float() / dim))

t = torch.arange(max_seq_len).type_as(inv_freq)

freqs = torch.outer(t, inv_freq)

# These buffers will be real tensors

self.register_buffer("cos_cached", freqs.cos(), persistent=False)

self.register_buffer("sin_cached", freqs.sin(), persistent=False)

def forward(self, x, seq_len=None):

# Calculation proceeds using real cached values...

return apply_rotary_pos_emb(x, self.cos_cached, self.sin_cached)Another idea is to have a init_constants(…) method on your top-level nn.Module subclass that can recursively initialize all such tensors on sub-modules.

Finally, to flesh out the meta model with real weights, you can do load_state_dict(..., assign=True) later.

FWIW this idea isn’t new, and is used extensively in libraries like HuggingFace’s accelerate to load massive models on consumer hardware.

Mmap-ing weights & reuse across representation

Another trick I settled on is mmap (memory mapping). It is possible to mmap the state_dict of a PyTorch Module so that the weights are mapped directly from disk instead of residing in RAM.

This is especially useful with PyTorch-related infra like torch.export. The compiler can just re-use this data (by pointing to it within the ExportedProgram) instead of allocating new memory.

Here a utility I wrote to handle this:

def move_model_to_disk(

model: torch.nn.Module, path: str = "temp_weights.pt"

) -> torch.nn.Module:

"""

Moves a model's parameters from RAM to disk-backed mmap tensors.

This function:

1. Saves current parameters to disk

2. Reloads as mmap'd tensors (zero-copy from disk)

Args:

model: The model whose parameters should be moved to disk

path: Path to save the weights file

Returns:

The same model, now with mmap-backed parameters

"""

import os

# Ensure directory exists

os.makedirs(os.path.dirname(path) or ".", exist_ok=True)

# 1. Save ONLY parameters (avoid moving buffers to disk if not needed)

params_only = {k: v for k, v in model.named_parameters()}

torch.save(params_only, path)

# 2. Load the raw tensors (mmap) & re-wrap as Parameters.

# mmap=True ensures we just map the file into virtual memory

mmap_sd = torch.load(path, map_location="cpu", mmap=True)

new_state_dict = {}

for name, tensor in mmap_sd.items():

# This wrapper shares the storage (no copy), preserving the mmap

new_state_dict[name] = torch.nn.Parameter(tensor, requires_grad=False)

# 3. Assign (strict=False is needed because we intentionally left out buffers)

# assign=True is critical: it replaces the tensor logic rather than copying data in.

model.load_state_dict(new_state_dict, assign=True, strict=False)

return modelThis works great if your ML compiler can also re-use this memory for its internal graph representation instead of allocating new buffers.

Note that this mmaping isn’t great for *inference*—you might hit page faults during execution which kills latency—but it works perfectly fine when *lowering* models (which is the point of an ML compiler).

Ideally, do this after any graph mutations (in PyTorch or otherwise) such as fusions. That way, the state_dict is stable and doesn’t need to be mutated further, preventing Copy-on-Write events.

Aggressively tracking & reducing object lifetimes

It is surprisingly easy to keep objects referenced longer than they should be.

A lot of times when prototyping ML infra, we tend to keep references to the “original” graph for debugging or traceability (e.g., node.meta[’source’] = old_node). Some of these culprits were my own code contributions from over a year go…go figure. If one isn’t careful, you end up keeping the entire original graph (and its weights) around for the lifetime of the compiler. Obviously this is very sub-optimal.

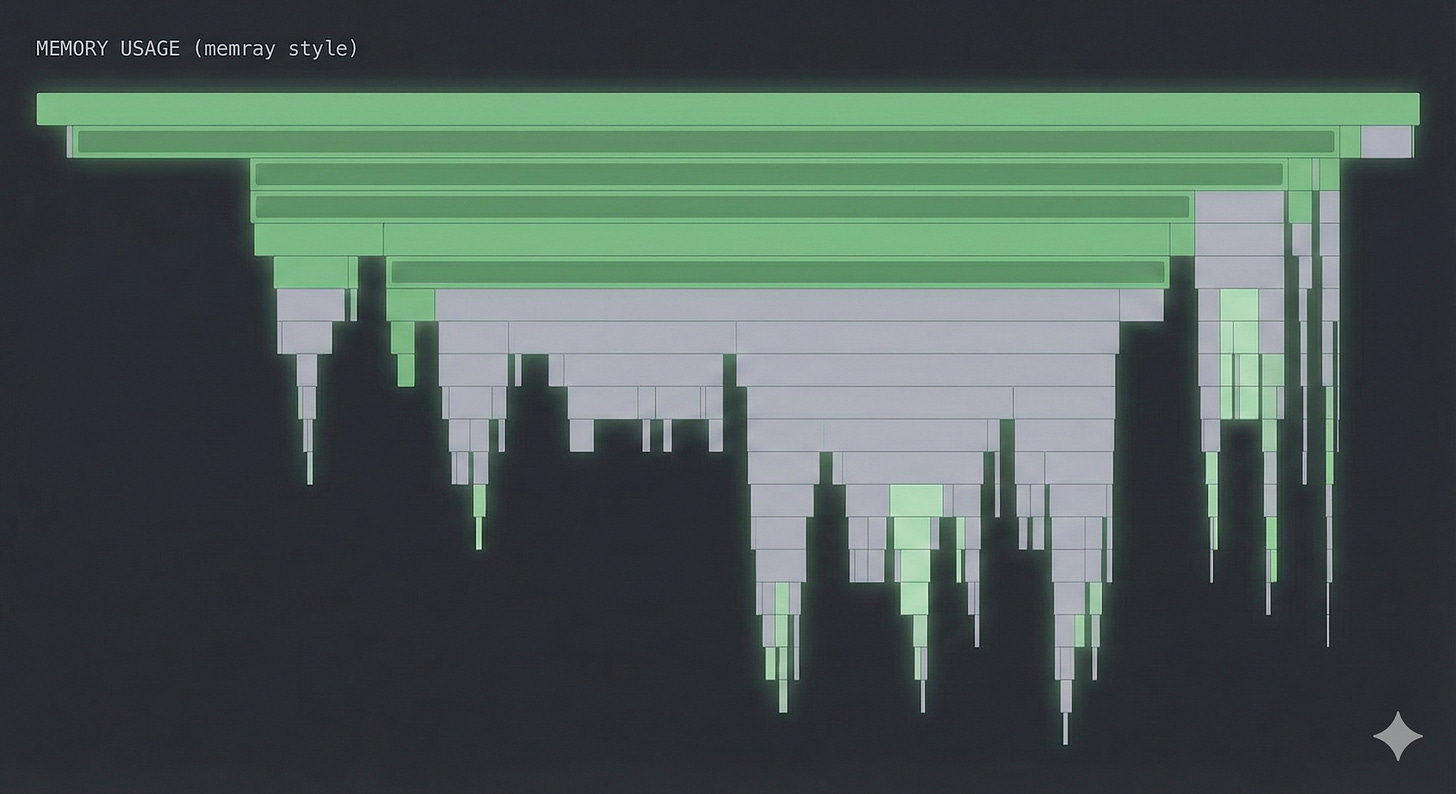

I found it incredibly useful to audit this with tools like memray. Unlike Python’s built-in tracemalloc, memray also tracks allocations in C/C++ extensions, which is vital since PyTorch is mostly C++ under the hood. It shows total peak allocations and exactly where they come from.

To verify my memory usage, I usually run:

# Run with --native to catch the PyTorch C++ allocations

memray run --native compiler_script.py

# Generate a flamegraph to visualize the heavy hitters

memray flamegraph memray-compiler_script.py.binIf you see a massive flat bar at the bottom of your flamegraph that persists throughout the execution, you are likely holding onto a reference you should have dropped.

Note that using a tool like memray is something of an onion-peeling experience, since one peak allocation usually hides another…so you likely end up hacking across your stack to get the end-to-end bloat down.

Being careful about virtual memory

Even though virtual memory is huge in modern systems (my 64GB M4 Max MBP at work rarely complains about swap), the system can still run out of it if your process asks for too much….and that’s all too easy when working with large foundation models on-device.

An example: there is a difference between “anonymous” memory (standard malloc) and “file-backed” memory. If you are writing custom compiler passes in C++ (common in LLVM based stacks), you have choices. Using llvm::sys::Memory::allocateMappedMemory creates anonymous mappings which count against the system’s “commit charge.” If this exceeds physical RAM + Swap, the OS kills you…you can see this gradually happen in something like macOS’ Activity Monitor.

In contrast, using llvm::sys::fs::mapped_file_region creates a file-backed mapping. Since these pages are backed by a file on disk, the OS treats them as “clean”—it can evict them instantly if pressure gets high without needing to write to swap.

// 1. The memory-pressure heavy way (Anonymous)

// Counts against commit charge. Can OOM if you allocate 100GBs

// even if you don't touch it all.

std::error_code EC;

llvm::sys::MemoryBlock block = llvm::sys::Memory::allocateMappedMemory(

size, nullptr, llvm::sys::Memory::MF_READ | llvm::sys::Memory::MF_WRITE, EC

);

// 2. The OS-friendly way (File-backed)

// Pages can be evicted freely. Great for loading huge weights.

int fd = open("weights.bin", O_RDONLY);

std::error_code EC;

llvm::sys::fs::mapped_file_region region(

fd, llvm::sys::fs::mapped_file_region::readonly, size, 0, EC

);There are other ways to get around this, like madvise …but that’s a tangent.

Parting thoughts

Optimizing the toolchain that optimizes the model is just as important as optimizing the model itself. If the tools are too heavy, you limit the complexity of the models you can experiment with on real-world hardware.

I had a lot of fun learning about the stuff described above, especially since I hadn’t worked with any of that before - its only now that we on-device ML engineers have to be mindful about resources even on laptops because the models are stretching the limits of our previously held notions :-).